Ex-utero Intrapartum Treatment (EXIT) – also known as ‘operation on placental support’ (OOPS) and airway management on placental support (AMPS)- is a rare surgical procedure, [1] performed to allow surgical correction of foetal airway patency whilst still being perfused by placenta. It consists of partial externalisation of the foetus from the uterine cavity during delivery, while maintaining placental circulation eliminating concerns for hypoxia. Currently in the UK, the EXIT procedures are undertaken in specialised centres, these include St. Georges Hospital London and Royal Manchester Children Hospital. In this article, Dr Sher Mohammad and other discuss the practicalities and challenges of managing exit-anaesthesia.

Advances in prenatal early diagnosis of foetal congenital airway malformations identify those that will benefit from this intervention. This, together with the concurrent advancements of surgical techniques, has resulted in improved survival for babies with airway obstruction that would make spontaneous ventilation or placement of an endotracheal tube after delivery impossible [2].

In 1989, Norris and colleagues [3] first attempted to manage the airway of a foetus with a large cervical teratoma. The foeto-placental circulation could be maintained only for 10 minutes, after which the foetus’ condition deteriorated. It is unclear whether the infant was fully or partially delivered, but rigid bronchoscopy and tracheotomy were attempted without success and the infant died.

Since then, the indications for EXIT procedures have expanded to include a variety of foetal congenital abnormalities outlined in table-1.

Table-1: Outlines the Indications for EXIT procedure

How different is EXIT procedure from caesarean section

In older text books e.g. Wylie and Churchill Davidson, there are two terms mentioned in obstetric section: I-D interval (Incision to Delivery time) which should be approximately 3 minutes; and U-D interval (Uterine incision to Delivery time) of 30-60 seconds.This was to minimise foetal exposure to anaesthetic agents. Moreover, a lower concentration of inhalational agents prevents loss of uterine tone and reduces the potential for haemorrhages.

In contrast, during the EXIT procedure tocolysis is the primary goal as the uterus is sensitive to handling and hysterotomy. This is achieved by increasing the MAC>1.5 to ensure a motionless, surgically anaesthetised foetus [4].

The use of high concentrations of inhalational agents in the mother often results in foetal anaesthesia. Intentionally long induction to incision times have been used for this. Although the foetus is anaesthetized with this technique, some authors have concerns about foetus not being anaesthetised (BIS monitor indicates depth of GA in mother only).

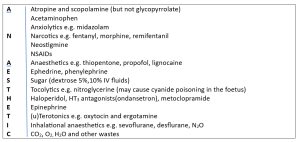

Any chemical with a molecular weight less than 500 Da, lipid soluble and non-ionised can cross the placenta easily. Many anaesthetic drugs used during RA, GA or even sedation easily cross placenta. In general, drugs which cross the blood brain barrier will cross the placental barrier as well. Drugs used during general anaesthetics which cross the placental barrier are outlined in table-2.

Table-2 showing list of ANAESTHETIC drugs which can cross placenta

The anaesthetist’s tasks:

- Preventing uterine contractions that would impair foetal oxygenation and cause placental separation (e.g. ketamine increases uterine tone)

- Maintain utero-placental perfusion

- Ensure foetal anaesthesia to help airway manipulations by perinatal ENT surgeon.

Traditionally, general anaesthesia (GA) has been the technique of choice for EXIT procedures due to the ease of titration of inhalational agents to achieve satisfactory uterine relaxation and to provide foetal anaesthesia. However, several reports have described neuraxial anaesthesia use in combination with tocolytics to achieve satisfactory operating conditions for EXIT procedure. The tasks and aims of anaesthetist are outlined as:

Managing exit-anaesthesia (GA)

The patient and foetus will need to be appropriately risk assessed [5]. Standard laboratory tests are performed, and prophylactic medications including antiemetics, sodium citrate, and ranitidine are administered [5]. The patient is positioned in a left uterine displacement supine posture to mitigate aortocaval compression [6].The EXIT procedure necessitates meticulous anaesthetic planning for the safety of both the mother and foetus.

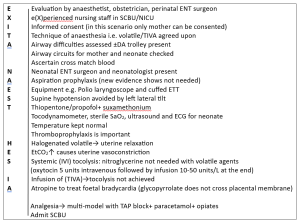

Given the general considerations of avoiding foetal exposure to unnecessary medications and potential protection of maternal airway, RA is usually preferred during pregnancy when it is practical for medical and surgical condition. However, in this particular scenario the anaesthetist is reluctantly compelled to administer higher doses of volatile anaesthetics (1.5-2.0 MAC) to achieve surgical anaesthesia in the foetus [7]. Administering anaesthesia during EXIT procedure is one of the few situations in which anaesthesia impacts more than one individual i.e. mother and the foetus at the same time. Table-3 outlines the management of general anaesthesia for EXIT procedure.

Table-3 outlines the technique of EXIT-ANAESTHESIA

Advantages of Volatile GA

V Volatile vapours→ tocolytic agents not needed

V Volatile vapours (cross placenta) →foetal anaesthesia

Disadvantages of GA

A Airway difficulties

A Aspiration risk

A Accidental awareness

A Analgesia not adequate

A Atonic uterus →postpartum bleeding→ blood transfusion

Regional anaesthesia ±remifentanil

Remifentanil rapidly crosses the placenta providing excellent foetal immobilization and is rapidly metabolized by foetal nonspecific blood and tissue esterase. It also acts as a good anxiolytic for an awake parturient mother, and is easily titratable to avoid excessive sedation in the presence of a high risk of aspiration.

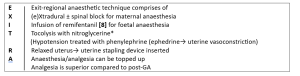

Table-4 outlines the management of EXIT-RA Technique

* NTG is most commonly used as a loading dose, ranging from 25–100 µg(onset 30-60 seconds) followed by an infusion at a rate of 1–20 mcg/kg/min to keep the uterus adequately relaxed. Pharmacokinetic studies have demonstrated that placental transfer of NTG has no significant foetal hemodynamic effects. This is most likely due to the short half-life and rapid placental metabolism of the drug [9,10].

Advantages of RA

Airway problem, aspiration risk, accidental awareness avoided (maternal problems)

Analgesia with RA is superior (maternal but foetal)

Disadvantages of RA

Relaxation of the uterus→ nitroglycerine needed

Foetal anaesthesia not achieved→ remifentanil infusion needed

RA+NTG→ hypotension and uterine hypoperfusion

Anxious mom watching Foetus being operated upon

PDPH chances increased

Discussion and conclusion

From the above description, it is obvious that the goals of exit-anaesthesia are maternal anaesthesia, foetal anaesthesia and tocolysis. Regional technique achieves maternal anaesthesia only; TIVA will give maternal as well as foetal anaesthesia, whilst volatile GA will provide all three components of exit-anaesthesia.

Literature review has shown that successful anaesthetic management of the EXIT procedure is possible with both GA and RA. However, there is a significant preponderance towards GA. The preference for GA for EXIT procedures can be explained by a number of reasons. A major goal of EXIT is profound uterine relaxation. Inhalational anaesthetics provide reliable and titratable uterine relaxation at MAC >1.5-2.0 with relatively quick reversibility [11].

Neuraxial techniques require additional IV nitroglycerine for uterine relaxation that can lead to problematic hypotension and uterine hypoperfusion. It is anticipated that the patients managed with RA+nitroglycerine will need more vasoconstrictors in the form of metaraminol or phenylephrine. Nevertheless, vasopressors are also needed while these patients are managed with general anaesthesia. EXIT procedure for the management of congenital diaphragmatic hernias is now infrequently performed due to alternative foetoscopic techniques. Foetal airway surgery management remains the main indication for EXIT procedure. Overall mortality in one study was 24% whilst the EXIT interventions themselves had low immediate ‘procedure-specific’ mortality (4%). This suggests that subsequent mortality is related to other perinatal factors. Recent developments also include use of 3D modelling for simulation and MDT training before embarking on the procedure.

Conflict of Interest: None Declared

Authors and Contributors:

Dr. Sher Mohammad1,Dr.Parhaizgar Khan2, Dr. Mujahid Ul Islam3 Dr.Mohammad Javed Khan4,

Dr. Zafar Iqbal5, Dr. Tariq Mahmood6, Dr. Salman Yahya7, Dr. Gul Rukh8

1.Consultant Anaesthetist(retired), STH NHS FT Sheffield

2.Prefessor of Anaesthesia, Pak International Medical College, Peshawar

3.Professor of Anaesthesia, Rehman Medical College, Peshawar

4.Associate Professor of Anaesthesia, Khyber Teaching Hospital, Peshawar

5.Consultant Anaesthetist, MMC General Hospital, Peshawar

6.Assisstent Professor of Anaesthesia, Imran Idrees Teaching Hospital, Sialkot

7.Consultant Anaesthetist(locum), York and Scarborough Teaching Hospitals NHS FT

8.Year-4 Trainee Anaesthetics, Khyber Teaching Hospital, Peshawar

Correspondence Address: smyousafzai@doctors.org.uk

References:

- E.D Skarsgard et al. The OOPS procedure (operation on placental support): in utero airway management of the foetus with prenatally diagnosed tracheal obstruction Journal of Paediatric Surgery (1996)

- 1.Ref. OA, O. (2009). Anaesthesia for EXIT procedure: A review. SAJAA, 15(1), 17-21.

- MC Norris, J Joseph, BL Leighton Anaesthesia for perinatal surgery Am J Perinatol, 6(1989) pp. 39- 40 View at publisher Cross ref View in Scopus Google Scholar

- Lee IH, Kim DY, Chung RK, Kim CH. Maternal and neonatal effects of sevoflurane and desflurane in caesarean section. Korean J Anesthesiol 2008; 55: 446-51.

- Bandyopadhyay K, Prabhudesai A, De A, Bhattacharya J. Anaesthesia for foetal surgery – principles and considerations: A concise review. Indian J Appl Res. 2023;13:14–16.

- Olutoye OA. Anaesthesia for the EXIT procedure: A review. Southern African J Anaesth Analg. 2009; 15:17–21. [Google Scholar2. R Dwyer et al.

- R Dwyer 1,J P Fee,J Moore Affiliations Expand,PMID: 7734253DOI: 10.1093/bja/74.4.379

- Intravenous remifentanil: placental transfer, maternal and neonatal effects, R E Kan 1, S C Hughes, M A Rosen, C Kessin, P G Preston, E P Lobo PMID: 9637638 DOI: 10.1097/00000542-199806000-00008

- MacKenzie TC, Crombleholme TM, Flake AW. The ex-utero intrapartum treatment. Curr Opin Paediatr 2002; 14: 453-8.

- Clark KD, Viscomi CM, Lowell J, Chien EK. Nitroglycerin for relaxation to establish a foetal airway (EXIT procedure). Obstet Gynecol 2004; 103: 1113-5.

- The Effects of Volatile Anesthetics on Spontaneous Contractility of Isolated Human Pregnant Uterine Muscle, Yoo, Kyung Y. MD, PhD*; Lee, Jun C. MD*; Yoon, Myung H. MD, PhD*; Shin, Min-HO MD†; Kim, Seok J. MD*; Kim, Yoon H. MD, PhD‡; Song, Tae B. MD, PhD‡; Lee, JongUn MD, PhD§ Anesthesia & Analgesia 2006. | DOI: 10.1213/01.ane.0000236785.17606.58103(2):p443-447