Dr Sher Mohammad and other authors discuss the anaesthetic implications and management of Restless Leg Syndrome, a chronic neurological sensory disorder that interferes with rest and sleep.

History and background

The first case report of Restless Leg Syndrome(RLS) was published in 1685 by Thomas Willis[1]. Karl Ekbom’s doctoral thesis “Restless Legs Syndrome: A Clinical Study of a Hitherto Overlooked Disease in the Legs Characterized by Peculiar paraesthesia (“anxietas Tibiarum”), Pain and Weakness and Occurring In Two Main Forms, asthenia Crurum Paraesthetica and asthenia Crurum Dolorosa”[1,2,3] was published in 1945. He was awarded with the Swedish Lennmalms Prize[4] for his work in 1949. For obvious reason, RLS has also been referred to as Willis-Ekbom syndrome.

Incidence and prevalence

RLS is a chronic neurological sensory disorder that interferes with rest and sleep. The prevalence of RLS is typically low in Asian countries and approximately 1-4% in Japan. It has a higher prevalence in women versus men. Early onset RLS has a peak incidence at 20-40 years of age, and a prevalence of 1.9% among children age 8-11 years.

Chemical disturbances leading to RLS

Although it is only partly understood, the pathophysiology of restless legs syndrome may involve dopamine and iron system perturbations. The interactions between impaired neuronal iron uptake and the functions of the neuromelanin-containing and dopamine-producing cells have roles in RLS development, indicating that iron deficiency might affect the brain dopaminergic transmissions in different ways (iron is a co-factor for L-DOPA which is a precursor of dopamine). Medial thalamic nuclei may also have a role in RLS as part of the limbic system modulated by the dopaminergic system which may affect pain perception. Improvement of RLS symptoms occurs in people receiving low-dose dopamine agonists(no longer first line of therapy though).

Primary and secondary RLS

Primary RLS is considered idiopathic and usually begins slowly, before approximately 40 years of age, and may disappear for months or even years. But it is often progressive and gets worse with age. RLS in children is often misdiagnosed as growing pains.

Secondary RLS often has a sudden onset after age 40. It is mostly associated with specific medical conditions such as trauma, surgery, pregnancy or certain diet/drugs.

Causes of and conditions associated with RLS

While the cause is generally elusive, it is believed to be caused by changes in the neurotransmitter dopamine resulting from an abnormal use of iron by the nervous system. Total body iron deficiency results in RLS which could be due to underlying anaemia caused by internal bleeding (e.g. menstrual) or bone marrow issues. Other associated conditions may include end-stage kidney disease and haemodialysis, folate deficiency, magnesium deficiency, sleep apnoea, diabetes/impaired glucose tolerance, peripheral neuropathy, Parkinson’s disease, and certain autoimmune diseases (multiple sclerosis). RLS can worsen in pregnancy, possibly due to high oestrogen levels. Use of alcohol, nicotine products, and caffeine may be associated with RLS. A 2014 study from the American Academy of Neurology also found that reduced leg oxygen levels were strongly associated with restless legs syndrome symptom severity in untreated patients. Genetics also play a role as more than 60% of cases of RLS are inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion with variable penetrance.

Research and brain autopsies have implicated both the dopaminergic system and iron insufficiency in the substantia nigra. Iron is well understood to be an essential cofactor for the formation of L-DOPA, the precursor of dopamine.

Both primary and secondary RLS can be worsened by surgery of any kind; however, back surgery or injury can be associated with causing RLS.

The cause vs. effect of certain conditions and behaviours observed in some patients (excess weight, lack of exercise) is not well established.

The causes of WILLIS-EKBOM disease are briefly outlined in table-1

Association with Psychiatric Comorbidities

An association has been observed between attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and RLS. Both conditions appear to have links to dysfunctions related to the neurotransmitter dopamine, and common medications for both conditions among other systems, affect dopamine levels in the brain. A 2005 study suggested that up to 44% of people with ADHD had coexisting RLS, and up to 26% of people with RLS had confirmed ADHD or symptoms of the condition [5].

RLS is strongly associated with psychiatric comorbidities, particularly depression and anxiety. Numerous systematic reviews and meta-analyses have demonstrated that individuals with RLS exhibit statistically significant higher levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms compared to healthy controls. The pooled prevalence of depressive states among those with RLS is approximately 30% and the frequency of depressive symptoms and suicidal thoughts is markedly elevated in this population [6-8].

Epidemiological studies further indicate that RLS is linked to a 2-4fold increased risk of developing major depressive and anxiety disorders, including generalised anxiety disorder and panic disorder [9-10].

Signs and symptoms

The uncomfortable sensations are experienced only when the limbs are at rest for any length of time, and they are typically relieved by movement. Patients state that they are experiencing an almost irresistible urge to move the legs and they may have to be walking around in order to get relief. Symptoms of RLS are very severe at times of immobility e.g. during train journeys, flights, at the cinema or the theatre. They are also especially troublesome in the late evening when patients are getting into bed. Sensations may last for hours but may also persist, with interruptions, in some unfortunate sufferers, until 3- 5 am. Patients often have to get up and walk around many times to obtain relief. This form of coping behaviour has been named ‘Night-walker′s syndrome’. Loss of sleep is a serious consequence both to patients and their spouses.

Restless legs syndrome is frequently associated with involuntary, rhythmic muscular jerks in the lower limbs: dorsiflexion or fanning of toes, flexion of ankles, knees and hips, so-called periodic limb movements (PLM) [11.12].

Onset of RLS may occur from childhood to >80 years of age [13]. The natural clinical course varies widely but RLS is generally regarded as a chronic condition with a successive increase of symptoms.

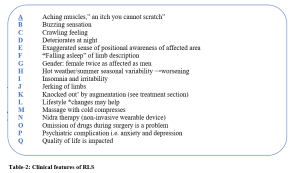

RLS occurs alone or with comorbidities, for example, iron deficiency and kidney disease, but also with cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus and neurological, rheumatological and respiratory disorders. RLS is poorly recognized by physicians and it is accordingly often incorrectly diagnosed and managed. The signs and symptoms outlined in table-2 are remembered as A, B, C……Q

*If RLS is not linked to an underlying cause, its frequency may be reduced by lifestyle modifications such as adopting improving sleep hygiene, regular exercises and quitting smoking. Iron rich foods include red meat, spinach, beans, dry fruit (add vitamin which helps absorb iron better). Folate rich food includes spinach, blacke-eyed beans, lentils, brussels sprouts, asparagus and rice. Magnesium rich food include spinach, black beans, brown rice, soy milk, almond, cashews and peanut butter. Tonic water containing quinine, coconut water and rooibos tea are helpful.

The NICE Guidelines February 2025 have included the IRLSSG approaches as follow:

The International RLS Study Group Assessment Guidance:

- Frequency of symptoms varies considerably from less than once a month to daily.

a) Chronic-persistent RLS is when symptoms, when not treated, would occur on average at least twice weekly for the past year.

b) Intermittent RLS is when symptoms, when not treated, would occur on average less than twice a week for the past year, with at least five lifetime events.

- Severity of symptoms can vary from mildly annoying to disabling.

The IRLSSG therefore state that, for clinical significance, the symptoms of RLS should cause significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, educational, or other important areas of functioning by their impact on sleep, energy, daily activities, behaviour, cognition, or mood.

- Consider using the validated symptom rating scale of the IRLSSG.This is completed by the person with RLS and then graded by the healthcare professional. The overall score gives an indication of severity: mild 1–10; moderate 11–20; severe 21–30; and very severe 31–40.

Investigations advised by IRLSSG

There are no investigations to confirm the diagnosis of restless legs syndrome (RLS).

- Request a full iron assessment including ferritin, total iron-binding capacity, and percentage transferrin saturation. This should be measured in the early morning after an overnight fast, as anaemia is not a sufficiently sensitive marker for iron deficiency, which may precipitate or exacerbate RLS.

- Consider other investigations guided by the history and examination (such as renal function, full blood count, thyroid function, blood glucose, folic acid, vitamin B12) to exclude secondary causes of RLS.

- Consider referring to a sleep clinic (if available) if you suspect a sleep disorder, and there is doubt about the diagnosis of RLS. Tests such as polysomnography can help to differentiate RLS from true sleep disorders.

Treatment options for RLS:

Physical measures

Stretching the leg muscles can bring temporary relief. Walking and moving the legs, as the name “restless legs” implies, brings temporary relief. In fact, those with RLS often have an almost uncontrollable need to walk and therefore relieve the symptoms while they are moving. Unfortunately, the symptoms usually return immediately after the moving and walking ceases.

Counter-stimulation from massage, a hot or cold compress, or a vibratory counter-stimulation device has been found to help some people with primary RLS to improve their sleep.

Iron therapy

There is some evidence that intravenous iron supplementation moderately improves restlessness for people with RLS. Sloand et al. showed that iron dextran infused in patients with end stage renal disease decreased RLS symptoms significantly when compared with placebo but the efficacy persisted only for 2 weeks [14]. Moreover, Grote et al. have shown that iron sucrose given intravenous in RLS works in the very short and longer term [15], and recently, the first double-blind, placebo-controlled study, on oral iron given over a 12 week period in RLS patients with low-normal ferritin values, demonstrated an improvement of RLS scores amongst those treated with iron [16].

Dopamine agonists are no longer the first line of treatment

Although dopaminergic treatment is initially highly effective, its long-term use can result in a serious worsening of symptoms known as augmentation.

Augmentation is a medical condition where the drug itself causes symptoms to increase in severity and/or occur earlier in the day. Dopamine agonists may also cause rebound when symptoms increase as the drug wears off.

Pramipexole and ropinirole are efficacious in long-term treatment of RLS [17,18]. Transdermal rotigotine (another non-ergot dopamine receptor agonist) has recently shown to relieve both night-time and daytime symptoms of RLS in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial [19].

Augmentation is seen in patients treated with pramipexole and ropinirole but at a lower rate than with levodopa. Interestingly, there were no signs of augmentation by 24 hour transdermal delivery of low-dose rotigotine [20].

Gabapentinoids are now the first line of therapy

Gabapentinoids (α2δ ligands), including gabapentin, pregabalin, and gabapentin enacarbil, are also widely used in the treatment of RLS. They are used as first-line treatments similarly to dopamine agonists, and as of 2019, guidelines have started to recommend gabapentinoids over dopamine agonists as initial therapy for RLS due to higher known risks of symptom augmentation with long-term dopamine agonist therapy. Gabapentin enacarbil is approved by regulatory authorities for the treatment of RLS, whereas gabapentin and pregabalin are used off-label. Data on gabapentinoids in the treatment of RLS are more limited compared to dopamine agonists. However, based on available evidence, gabapentinoids are similarly effective to dopamine agonists in the treatment of RLS.

Both the 2021 algorithm for the treatment of RLS published by members of the Scientific and Medical Advisory Board of the RLS Foundation in the Mayo Clinic Proceedings, and the2024

American Academy of Sleep Medicine Practice Guidelines recommend the use of low-dose opioids for the treatment of refractory RLS, with the caveat that, although opioids are highly effective, “reasonable precautions should be taken in light of the opioid epidemic. Among the opioids and their suggested doses are tramadol, codeine, morphine, oxycodone, hydrocodone, methadone (all of which are schedule II), and buprenorphine (a schedule III partial opioid-receptor agonist with a lower risk of causing respiratory depression or dependence, compared with the full-agonist opioids).

Gabapentin has been reported to be efficacious in treating RLS [20]. Moreover, Happe et al. reported that gabapentin was as effective as ropinirole in reducing PLM and improving sensorimotor symptoms in patients with primary RLS [21]. A novel gabapentin prodrug, XP13512 1.200 mg taken once daily, has also been recently shown to improve RLS symptoms compared with placebo after 12 weeks of treatment [22].

Other treatments

Other treatments have also been explored, such as valproate, carbamazepine, perampanel, and dipyridamole, but are either not effective or have insufficient data to support their use.

Anaesthetic and peri-operative strategies

Anaesthetic implications for patients suffering with RLS are multiple. In sufferers, perioperative movements may be deleterious to the surgical outcome.

In procedures normally performed under regional anaesthesia, necessitating stillness, alternative techniques should be sought. Serum ferritin levels mirror the severity of the condition; thus, bleeding may worsen the condition. Raux et al [23] suggest monitoring postoperative serum ferritin levels, with replacement either orally or intravenously in those with low levels below 50 mg/ml.

RLS can be triggered by metoclopramide, droperidol and chlorperazine, and their use for prevention of nausea and vomiting should be avoided in these patients. The use of domperidone and 5HT-3 receptor antagonists is safe. Non-drug management of PONV will be useful.

Anxiety about surgery and anaesthetic intervention can alter the physiology and disrupt routine medicine intake. Major surgery may cause limitation of movement, sleep disturbance and blood loss leading to anaemia and iron deficit.

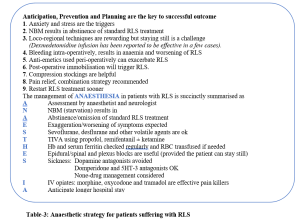

The two main peri-operative problems are worsening of symptoms and management of pain relief. Chronic iron deficiency should be corrected with iron supplements, similarly folate and magnesium levels checked and corrected. Continue the drug treatment of RLS and resume as soon as possible. Table-3 succinctly outlines the anaesthetic strategy.

Latest AASM Guidelines 2024

RLS is a sleep-related movement disorder characterised by a strong, nearly irresistible urge to move the legs, which is often accompanied by other uncomfortable sensations felt in the legs. These symptoms begin or worsen during periods of rest or inactivity, are temporarily or totally relieved by movement, and occur exclusively or predominantly in the evening or at night. RLS can cause sleep disturbance, distress, and impairment in functioning.

One of the significant changes in the new guideline is that it elevates the importance of iron evaluation in everyone with RLS and, depending on iron indices, recommends iron supplementation. These recommendations reflect evidence suggesting that low brain iron is an important underlying cause of RLS. For adults with RLS, the guidelines provides a strong recommendation for intravenous ferric carboxymaltose and conditional recommendations for two other formulations of intravenous iron and one formulation of oral iron — ferrous sulphate. For children with RLS, ferrous sulphate received a conditional recommendation, making it the only treatment recommended for paediatric patients [24].

Conflict of Interest: None Declared

Authors and Contributors:

Dr. Sher Mohammad1, Dr. Ajmal Khan2, Dr. Hayat Khan3, Dr. Aziz ur Rahman4, Dr. Hafiz Murad Khan5, Dr. Zafar Iqbal6, Dr. Jawad Hameed7, Abdul Zahoor8

- Consultant Anaesthetist(retired), STH NHS FT, Sheffield.

- Consultant Rheumatologist, Neima Healthcare Centre, Al Ain UAE

- Consultant Psychiatrist in CAMHS, Calderdale and Kirklees CAMS, South West Yorkshire NHS FT Folly Hall Mills, St. Thomas Road, Huddersfield

- Anaesthetist Tipperary University Hospital, Clonmel, Ireland

- Consultant Anaesthetist, Bahrain Defence Force Hospital, Kingdom of Bahrain.

- Consultant Anaesthetist, MMC General Hospital Peshawar

- Assistant Professor of Anaesthesia, Lady Reading Hospital Peshawar

- Dr.Abdul Zahoor, Senior Consultant Anaesthetist. King Khaled Specialist Hospital, Riyadh Saudi Arabia

Dr. Hayat Khan, Consultant Psychiatrist in CAMHS, Calderdale and Kirklees, covered the psychiatric aspects of this article.

Correspondence Address: smyousafzai@doctors.org.uk

References

- Coccagna, G; Vetrugno, R; Lombardi, C; Provini, F (2004). “Restless legs syndrome: anhistoricalnote”. SleepMedicine. 5(3): 279–83. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2004.01.002. PMID15165536.

- “Biography of KA Ekbom”.Archived from the original on 2016-06-30.Retrieved 2016-06-07.

- Ekbom, Karl-Axel (2009). “PREFACE”. Acta Medica Scandinavica. 121: 1–123. doi:10.1111/j.0954-6820. 1945. tb11970.x.

- List of winners of the Lennmalms PriceArchived 2016-08-07 at the Wayback Machine

- D P Migueis 1, M C Lopes 2, E Casella 3, P V Soares 4, L Soster 5, K Spruyt 6 PMID: 36924608 DOI: 10.1016/j.smrv.2023.101770

- Association of Anxiety and Depression With Restless Leg Syndrome.A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. An T, Sun H, Yuan L, Wu X, Lu B. Frontiers in Neurology.2024;15: 1366839.DOI:10.3389/fneur.2024.1366839

- Prevalence of Depression or Depressive States in Patients With Restless Leg Syndrome.A Systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Miyaguchi R, Masuda F, Sumi Y, et al. Sleep Medicine Reviews.2024;77: 101975. DOI: 10.1016/j.smrv.2024.101975.

- Depressive Symptoms and Suicidal Thoughts in Restless Leg Syndrome. Chenini S, Barteau L, Guiraud L, et al. Movement Disorders. Official Journal of Movement Disorder Society.2022,37(4)812-825.DOI:1002/mds.289903.

- Depressive Disorders in Restless Leg Syndrome: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology and Management.Hornyak M.CNS Drugs.2010;24(2):89-98.DOI:10.2165/11317500-0000000000.

- “Anxietas Tibiarum”. Depression and Anxiety Disorders in Patients With Restless Leg Syndrome. Winkelman J, Prager M, Lieb R, et al Journal of Neurology.200;252(1):67-71.DOI:10.1007/s00415-005-0604-7

- Lugaresi E, Tassinari CA, Coccagna G, Ambrosetto C. Particularités cliniques et polygraphiques du syndrome d ′impatiences des membres inférieurs. Rev Neurol 1965; 113: 545–55.

- Coleman RM. Periodic movements in sleep (nocturnal myoclonus) and restless legs syndrome. In: C Guilleminault, ed. Sleeping and Waking Disorders: Indications and Techniques. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley, 1982; 265–95.

- Allen RP, Picchietti D, Hening WA, Trenkwalder C, Walters AS, Montplaisir J. Restless legs syndrome: diagnostic criteria, special considerations, and epidemiology. Sleep Med 2003; 4: 101–19.

- Sloand JA, Shelly MA, Feigin A, Bernstein P, Monk RD. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of intravenous iron dextran therapy in patients with ESRD and restless legs syndrome. Am J Kidney Dis 2004; 43: 663–70.

- Grote L, Leissner L, Hedner J, Ulfberg J. A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled, multi-center study of intravenous iron sucrose and placebo in the treatment of restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord 2009; 24: 1445–52.

- Wang J, O′Reilly B, Venkataraman R, Mysliwiec V, Mysliwiec A Efficacy of oral iron in patients with restless legs syndrome and a low-normal ferritin: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Sleep Med 2009; (Epub ahead of print); doi:DOI: 1016/j.sleep.2008.11.003.

- Montplaisir J, Fantini ML, Desautels A, Michaud M, Petit D, Filipini D. Long-term treatment with pramipexole in restless legs syndrome. Eur J Neurol 2006; 13: 1306–11.

- Garcia-Borreguero D, Grunstein R, Sridhar G et al. A 52-week open-label study of the long-term safety of ropinirole in patients with restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med 2007; 8: 742–52.

- Trenkwalder C, Benes H, Poewe W et al. Efficacy of rotigotine for treatment of moderate-to-severe restless legs syndrome: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 2008; 7: 595–604.

- Garcia-Borreguero D, Larrosa O, De La Llave Y, Verger K, Masramon X, Hernandez G. Treatment of restless legs syndrome with gabapentin: a double-blind, cross-over study. Neurology 2002; 59: 1573–9.

- Happe S, Sauter C, Klösch G, Saletu B, Zeitlhofer J. Gabapentin versus ropinirole in the treatment of idiopathic restless legs syndrome. Neuropsychobiology 2003; 48: 82–6.

- Kushida CA, Becker PM, Ellenbogen AL, Canafax DM, Barrett RW, for the XP052 Study Group. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of XP13512/GSK 1838262 in patients with RLS. Neurology 2009; 72: 439–46.

- Raux M. Case Scenario: Anaesthetic implications of RLS Anaesthesiology.2010;112(6):1511-1517

- Winkelman JW, Berkowski JA, DelRosso LM, et al. Treatment of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2025;21(1):137–152.

Image: Canva